Approximately two out of every five students in the U.S. cannot read at a basic level. Literacy rates have been declining for more than a decade but since the COVID-19 pandemic— those rates have gotten worse.

The ability to read and write is fundamental. Without these necessary skills, students are falling behind and their future success is a concern. In Monroe County, less than 40% of third to eighth grade students are proficient in reading.

For Carol St. George, these aren’t just numbers, they reflect the deeper issues within education. St. George directs the literacy teacher education program at the Warner School of Education and teaches courses in teaching and curriculum related to theory and practice for reading professionals.

As a veteran K-12 teacher, a mother of three and current professor St. George has watched the conversation and instructional strategies change over the years. Recently, she has noticed the lack of literacy recognition in kids’ regular routine.

St. George recalls a day she was reading with a first-grade class. While the group was reading one student in particular, Leah, stuck with St. George.

“If they came to a word they didn’t know as we were reading together, they’d look at me— that was their strategy,” St. George said. “They were afraid to take a chance, to take an educated risk. You can’t blame them. People are afraid. I’m afraid to be embarrassed if I don’t know something, right.”

Leah used this very strategy when she came upon the word “saw.” St. George explained what the word meant, but realized many of the students did not know the word. Leah made a hand gesture in a sawing motion. To these students “saw” was a tool not something you witness or perceive.

“I realized that it wasn’t in her vocabulary, it was ‘I seen it’,” St. George said. “It was like an epiphany for me. I find now, literacy starts pre birth,” St, George said.

St. George noted babies cry in the melody of their native language. Many studies show human fetuses are able to memorize auditory stimuli from the external world by the last trimester of pregnancy, with a particular sensitivity to melody contour in both music and language.

This blew St. George’s mind as it revealed other factors that may add to this crisis.

“I was wild by it,” St. George said. “I found that a few years ago, but then that proves that language is developing in utero. It’s not too early to start reading to your baby. And I’m saying, day one, start reading with your kid. People think I’m crazy. People say to me, ‘why would I talk to my baby? They can’t talk to me.’ But that whole idea of developing language is what in my opinion, in large part is contributing to the crisis that that we’re seeing.”

The “Belief Gap”

The NYSED ELA assessment data shows 46% of students from public and charter schools are proficient. In Monroe County many central school districts outperformed state and county averages including Honeoye Falls-Lima CSD, Penfield CSD and Fairport CSD. Other districts fell well below this average including Wheatland-Chili CSD and Rochester City SD.

Education Trust New York examined the belief gap. This research shows 95% of all students have the cognitive ability to read and write regardless of background. Countywide these outcomes are well below the 95% threshold.

The belief gap normalizes low expectations and unjustly accepts poor reading outcomes as a defining characteristic of students of color and those from low-income backgrounds.

“Every single person should see the importance, the value and the idea that your zip code should not determine the quality of your education or the access to materials. Include families with the teachers so they know how to support their kids at home,” St. George said.

Reading wars and the blame game

There has been a longstanding discussion surrounding the reading wars since the 1950s. The novel “Why Jonny Can’t Read” by Rudolf Flesch critiqued American reading instruction which produced widespread discourse across the country.

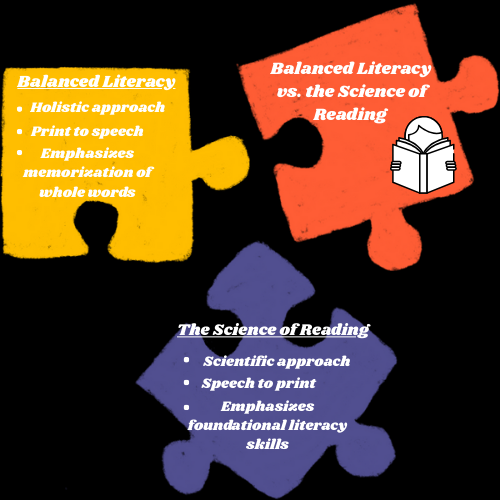

Flesch examined the decline in reading skills among American children in the 50s. He believed the failure to include phonics as a core reading skill was at the root of the issue. Flesch argued phonics was more effective than the “look-and-say” method (the whole language approach) because students learn the basic sounds of letters rather than memorizing entire words.

The reading wars emerged as a descriptor for this prevalent debate— whole language versus phonics. Although the conversation is still greatly centered around phonics, it has taken new shape— Balanced Literacy versus the Science of Reading.

Co-leader of Dyslexia Allies of Western NY and the coordinator for the Student Success Project Tina Carney, is also a Gates-Chili CSD parent. She is a graduate of the Greater Rochester Parent Leadership Training Institute and has longstanding concerns about the foundational concepts in the curriculum.

“When my oldest was in elementary school. It was balanced literacy. And at the time, I didn’t know what that was. It was the three cueing approach that we know is not evidence based. Unfortunately, years later when my child was struggling, teachers didn’t know what they didn’t know. Families put a lot of trust into schools, and this was one example of, well, multiple systems failures— it definitely didn’t serve my child. It was a disservice, and it didn’t serve quite a few others. But with the emergence of not only phonics, but also phonemic awareness is huge.”

Former deputy superintendent of teaching and learning and chief of schools for Rochester Demario Strickland, Ph.D., is now the acting Interim Superintendent of Schools for the Rochester CSD. He has seen the distinctions of Balanced Literacy and the Science of Reading.

“Whole language has been a big has had a big focus here in Monroe County and that’s actually why we’re having such a hard time with getting individuals to actually stay true and steadfast towards getting teachers to use research-based practices. If we continue to provide the professional development and give updates to our teachers that are in house and give the new learning to the teachers that are coming from our higher education institutions, I think we’ll be in a good spot,” Strickland said.

Carney has kept up on the changes within her own district and while she thinks there is still a long way to go, she is hopeful for the future.

“Schools have had to invest in professional development outside to essentially retrain teachers and staff. I did not think that I would see a change in my children, but I see the difference between my oldest and my youngest who are currently in elementary. It is a 180 change that has happened over the last four years and for that, I’m really grateful,” Carney said.

While this dispute focuses on teaching methodologies the conversation extends to who is to blame for declining literacy rates.

“I’ve been doing this a long time,” St. George said. “I remember when it was a parent’s fault. ‘Why can’t kids read?’ ‘The parents don’t read to their kids.’ Then it shifted, ‘it’s the teacher’s fault’ and now it’s ‘teacher preparation schools don’t teach teachers how to teach reading.’ So, I think that there’s misunderstanding, a lack of trust and I think there’s a lack of time.”

St. George has been in each position. She believes no one group should face the criticism. St. George views the ‘blame game’ as a clear indicator of the need for teacher-family relationships.

“This blame game has to stop. This isn’t a matter of the parents not doing their job. Can they do it better? You bet. And it’s not a matter of the teachers not doing their job. Can they do it better? Yes, you bet. Can the can we all do better? Yeah, and I think that it’s a matter of listening,” St. George said.

A large part of St. George’s dissertation work was workshops for teachers and parents. While the work was aimed to build a bridge, she found it shocking parents and teachers didn’t realize they’d be learning together.

“That’s why a lot of my work is in communities showing people how to build relationships, working and being visible. My relationship with families is crucial for children’s success,” St. George said.

The Curriculum

New York State’s (NYS) public school curriculum is clearly defined in the NYS School Boards Association Curriculum Guide.

In New York, curriculum must be aligned to the applicable state-mandated learning standard…The curriculum offered by school districts in their schools is a matter of educational policy within the discretion of a district’s school board.

The NYS State Education Department (NYSED) requires the annual ELA test under the federal Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA). This test measures student progress through listening, speaking, writing and reading to gauge the mastering of these skills used in classroom instruction.

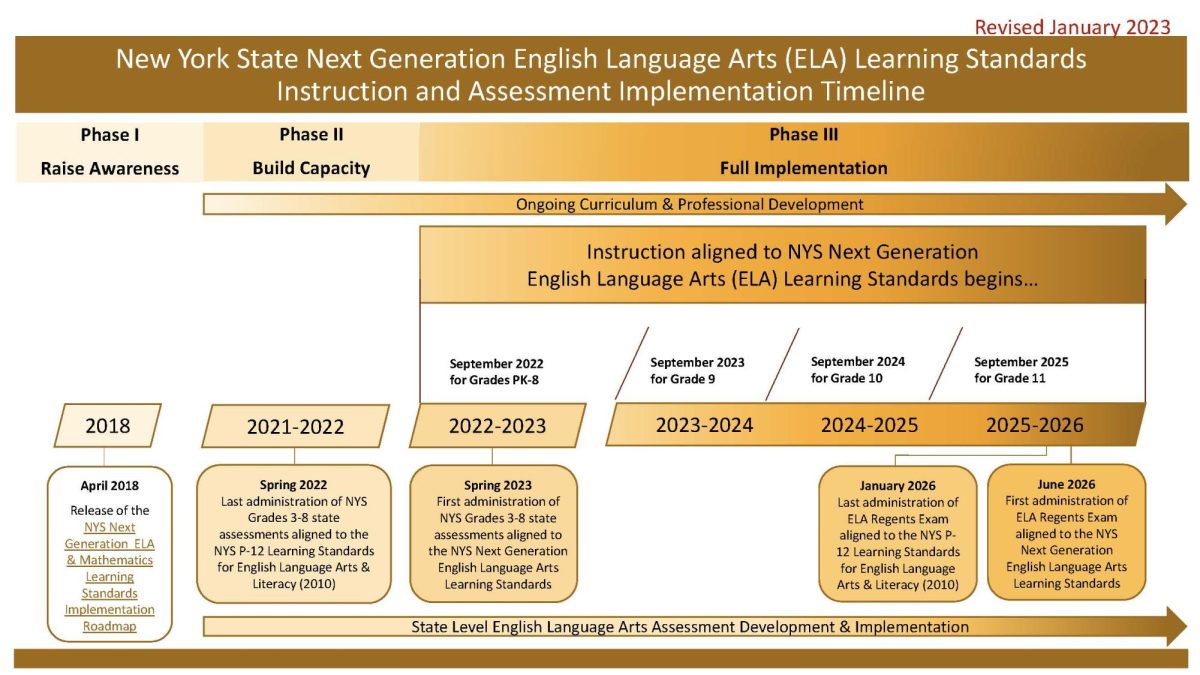

The NYSED initiated a gradual removal of the ELA Common Core Standards in 2022. Now the NYSED has implemented the Next Generation English Language Arts (ELA) Learning Standards Instruction. This three-phase plan gradually aligns with the ever-changing societal landscape to ensure better learning objectives for all students.

While this nuanced approach is still underway, parents and educators in Monroe County are continuing to look for sustainable solutions and tools to assist students in and outside of the classroom. Strickland has seen the changes in curriculum and is working toward a better foundation of literacy for students’ future success.

“Our current text that we use for K-5 is lacking,” Strickland said. “It has some gaps as it pertains to the five pillars of literacy. So, what we’ve done for K-2 and actually welding down to pre-K, have adopted a curriculum called Amplify, which is a skill strand that follows the science of reading. It’s extremely beneficial because it is research based really helping students to understand phonemes, how letters sound, how sounds make words, how to decode, you know bringing the sounds together to make words.”

Looking at higher grade levels Strickland believes the best way to combat students falling behind is through literacy initiatives like vocabulary development and comprehension. Strickland finds the investment of these initiatives for teachers is necessary to keep up with current changes.

“I’m pretty pleased with where we’re going with that. We continue to make investments and the language essentials for teaching teachers of reading and spelling, which is called Letters. All of our teachers are trained on the modules. It’s ongoing. It’s something that we now call maintenance,” Strickland said.

The Disconnect

While literacy proficiency rates differ across districts in Monroe County these outcomes concern many local parents. Carney is a mother of children who are neurotypical and neurodiverse. Carney believes she has learned much from both experiences but has noticed a lack of communication between the schools and families.

“There needs to be more transparency about how you’re teaching our kids to read, how you’re assessing our kids and where they are in comparison to their peers and the state as well. This provides opportunities for parents to come to visit the school and learn a little bit about what you’re teaching the students so we can reinforce it at home.”

After feeling frustrated and unable to do enough Carney wanted to get more involved. Now she works alongside many parents with a variety of lived experiences to better advocate not only for their children but all NYS students.

Carney recognizes it’s not easy as there are many barriers for school districts to do more but she believes the first step is engagement.

“This could be done on your own as a teacher. It could be done through the Parent Teacher Organizations (PTO). It could be done through Title I funds. Many districts receive title one federal funding, and within that is some really good policy about family engagement. It explicitly states in just about every policy I’ve read, ‘tell parents what you’re teaching, tell them how they’re assessing’ and so it’s in there,” Carney said.

Carney calls for more parent recognition as the students “first and core teacher”. While she puts an emphasis on what schools and teachers can be doing better, Carney also highlights the role parents must play.

“We need to focus on implementation, so for parents just be curious. Ask your district questions. What’s in your district? How are you teaching our kids to read? Is it aligned with the science? Is it aligned with what we know is the best? Stay curious,” Carney said.

Strickland while in a different district finds the best way to help students is through the parents.

“I think it starts off at the very beginning with helping them form parents or bringing parents to the table to actually discuss what they are seeing at homes. Even though we’re the experts, that doesn’t mean we’re the experts of those children. We have to understand that the parent is the first teacher. The parent is the expert of the child. We’re the expert practitioners that get them after they send them to us,” Strickland said.

Strickland sees the importance in transparency but realizes it’s not always done right.

“Putting out the ED reports on the curriculum so parents can read up on it to see if it’s meeting the needs of their children is absolutely necessary, and sometimes school districts don’t want to do that and it’s unfortunate,” Strickland said. “I’m not that kind of leader. I love bringing parents to the table. Once they are at the table, they will fight tooth and nail for you and for what you’re trying to do. Generally, that’s why I’ve had success in all the districts that I’ve been in because parents are a part of the decision making. And if you do that, which we should be doing then you won’t have an issue.”

A new way forward

While Strickland’s role as interim superintend will come to end in the coming months, he sees the possibilities to better literacy education.

“The next step is taking the time and opportunity to go to colleges and find out what are they teaching their preservice teachers, education majors and is it aligned to the science of reading. So, when those individuals get into the work force, they are not throwing their hands up and confused as to what it is that they need to do, which often happens,” Strickland said.

St. George is a proponent for a culture that is welcoming and enthusiastic about literacy as it would not just help students but the larger society to thrive.

“Literacy is everywhere once we open our eyes to the fact that. A lot of discussions about literacy and phonics, and I don’t want to be on the bandwagon to say phonics is not important for God’s sakes I know that. But without vocabulary building, without building a passion and a love and without allowing for motivation, then it’s going to be banging your head against the wall. You might give them the tools to decode, but decoding is not the same as reading… I want to saturate the area. I want billboards like, ‘have you read with your child today?’ Those are the kinds of messages that we as a community need to foster and support,” St. George said.

This crisis is shaped by many factors, but a renewed attention to find sustainable solutions like adaptive curriculum, literacy initiatives and parent-teacher collaboration is underway. These solutions may well give rise to a more literate society, but the road to combat this issue is continually changing and it demands a community effort to navigate. Although the future of literacy success is unknown, these Monroe County educators and parents are bringing the conversation outside classroom doors.

.