By Jessica Karcz

Many had turned to the arts for comfort throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, whether it was through television, music or simply putting a pen to paper. What many don’t see is what goes on behind the scenes. High unemployment and underfunding of the arts is not uncommon and many who choose to pursue a career in the arts are constantly working to get on stage. Four SUNY Brockport alumni take us through how they navigated a field in the arts and the challenges they face to make something they love, a career.

Ebony Vasquez, a 2020 SUNY Brockport graduate, was preparing to begin her career on tour as a member of the Garth Fagan Dance Company in Rochester, when the pandemic halted her performance season.

“It shut down every major performance we had. It stopped my life because I moved out here to dance with the company and after things got shut down I went home for about 5 to 6 weeks because there was nothing else to do,” said Vasquez.

At the beginning of the pandemic, Vasquez had to decide if she wanted to quit the company and move back to her home in New York City or get another job until the company decided to open its doors again.

“I have to adult now, so I have to maintain rent and utilities at a place where I was depending on the income of that job to pay rent. I had to decide whether I felt the company was worth it and stay out here and stick it out and find another job and find out what i’m going to do in the meantime or if they werent and put in my two weeks and go home,” said Vasquez.

Vasquez had made the decision to stay in Rochester and landed another job as a dance teacher at the Harley School in Rochester. Without her work study job on top of her new job, she was worried she would have not been able to stay and wait for the company.

“I felt like it was just the beginning of my career and though Covid was dreadful, I still had some classes to finish and I didn’t want to go back home, so I kind of had to figure it out. If it wasn’t for being a student and getting a refund or having a work study job that gives me some type of income, I wouldn’t have had anything to fall back on,” said Vasquez. “People think it’s so glamorous, it’s like no I just get to dance with a bigger name company but I’m still working 2 to 3 jobs, I’m still counting my hours”.

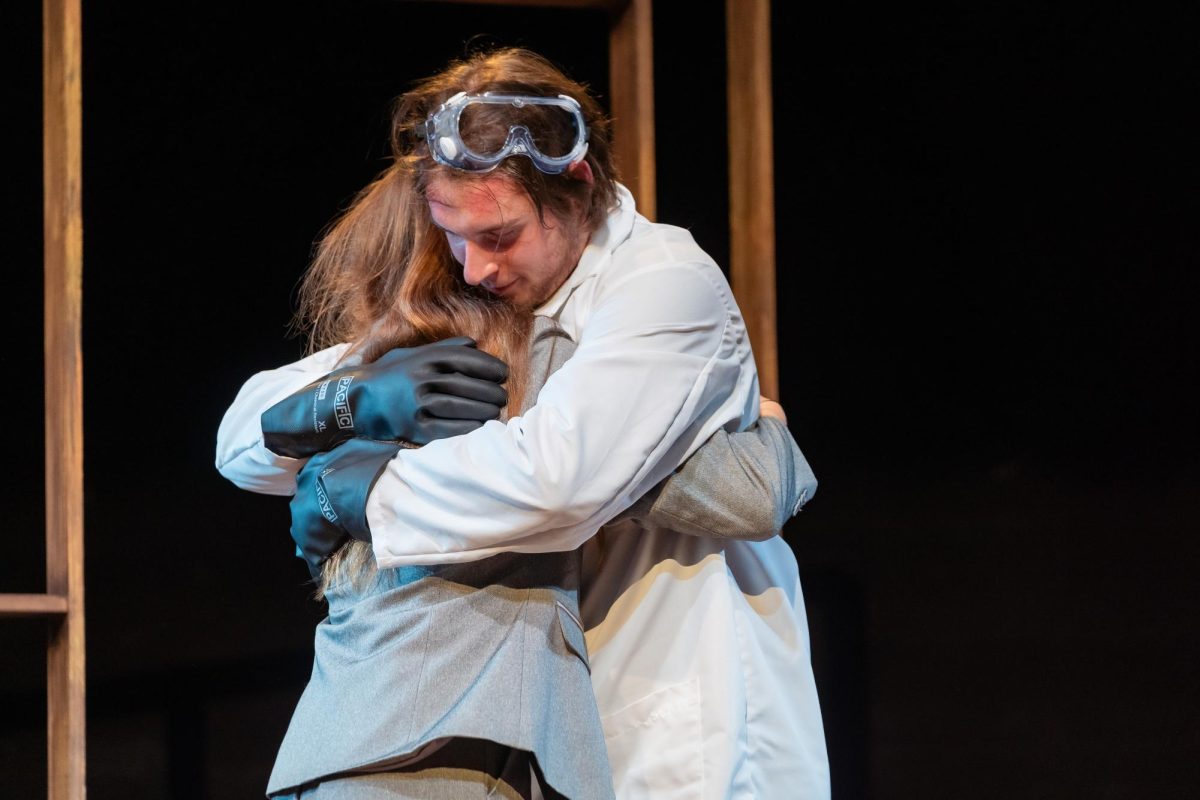

Zachary Frazee, director of Frazeefeetdance in Rochester has had their own experience struggling to make money right out of college and having to say yes to any gig that came their way.

“When I first graduated, there was a definite struggle to just making ends meet, you know, and that’s still something that comes and goes every now and then, but, it was saying yes to any possible opportunity that came my way, whether it was paid or not, just for the hope that it would bring about something that might lead to something else. You know, there’s always hope that it’s going to lead to something bigger, and sometimes it does, and sometimes it just falls flat,” said Frazee.

Dancers often have a hard time deciding which job is right for them and evaluating their own worth as a performer. Frazee believes problems stem from the dance industry and how it makes dancers conditioned to not feel worthy enough for a stable income.

“I feel within the industry, there’s this standard when you’re starting out, you don’t either deserve or haven’t earned the place to earn a certain amount of money or to make a certain amount for a gig for a contract which is complete bull because just the fact that you’re young doesn’t mean that you don’t have something unique or important to bring to the table.” said Frazee.

Claire Fisher, who has danced with Wildbeast Dance in Rochester and has brought her own choreography around the country has found most jobs she had in the past would not pay her for rehearsals she had to attend.

There is an ongoing problem where dancers will dance for free simply because they want to perform. They are also hoping this will give them more exposure to potential future employers. Caitlyn Mahon, an adjunct professor at Nazareth College in Rochester has seen this with her students and herself.

“Answers are so willing to be like ‘Oh yeah, I’ll dance for free, oh yeah, I just want to be performing so I’ll dance for free’. Whereas in other arts, when you work with live musicians or videographer’s right away, they’re like OK. What am I getting paid? And they negotiate. Why is that skill not inherently for us? ’cause then it hurts us in the long run. It hurts all of us,” said Mahon.

Frazee has experienced this themselves and since becoming more financially stable, has had to learn to say no to certain jobs for the sake of their own well-being.

“It took me a really long time to get to a spot where I was like, OK, I don’t need to say yes to all the things and do all the things just for the sake of either exposure or for a little extra money. I think there’s something to be said about setting boundaries for yourself as an artist. And I wish this is something that I’d learned or known when I was younger, because I, you know, did a lot of overwork myself, which you know did lead to injury and other sorts of things,” said Frazee.

Even with the hard work, dancers believe there is never a notion of becoming ‘successful’ in the professional dance world. These demands being put on them have caused a toll on their mental health.

“It’s always about the hustle, right? There’s always this idea that you need to be hustling all the time in order to like make it whatever that means ’cause that’s different for every person,” said Frazee.

Mahon has also felt the same way in the sense of “not making it” in the dance world.

“It’s a constant struggle. there’s never this notion of making it. You’re never gonna like, make it. It’s project by project. It’s constantly hunting and advocating for yourself. It’s exhausting. Yeah, and honestly that’s why we have to be so passionate and love what we do. Otherwise we’d be a little bananas, right? Like it’s so much extra work,” said Mahon.

When dealing with her own experiences, Mahon tries to reassure her students not to be too hard on themselves when training to dance professionally.

“What I tell my students all the time is 95 percent of the time you hear no. But there is that five percent. It doesn’t mean you’re not good enough. It doesn’t mean you’re not skilled. It doesn’t mean you’re not an artist, it’s just grueling. It’s really grueling,” said Mahon.

Dancers desire to see a change in the competitiveness of the dance industry, especially with the current COVID-19 pandemic forcing them to stay home.

“My hope is that, you know. As things start to break down a little bit more, and as more people start to talk about how the industry needs to change, hopefully these practices of constantly having to do everything all the time. People can really process and create in a way that’s mindful and filled with integrity versus just doing it. Not from a place of emptiness,” said Frazee.

Fisher wants to see change, as well and ends on a positive note that dancers continue to dance, despite all the hardships that might come with it.

“At times, it takes a toll on one’s mental and physical self, because the cycle can be draining. It’s always been about the grind and the hustle though. As a dancer, I think a lot of us as artists don’t do it just for the money, we dance for the love of the craft itself,” said Fisher, “The arts are appreciated by many, but it doesn’t help when funding for the arts is limited, or slim to none. It’s sad that is how it is, but I hope to see growth in these aspects in the future,” said Fisher.

Now with the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, dancers have begun advocating for a change in the way arts are funded and yet with these setbacks, dancers continue to work hard to make something they are passionate about their career.