By Maryalice Skutnik

In 1944, the United States was in the midst of World War II and the small town of Hamlin, NY played a significant role in supporting the war efforts. During this time, Hamlin Beach State Park was home to hundreds of German prisoners of war (POWs).

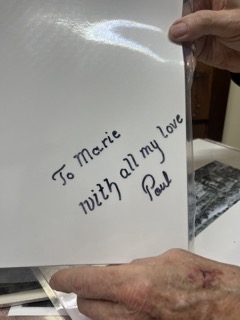

With some as young as 13 years old, these POWs were forced to work on farms and in canning factories for 85 cents a day. The first group of men to arrive at Hamlin’s POW camp came in June of 1944. Amongst them was a man named Heinrich Willert, who was able to later get in correspondence with Ed Evans.

“He enlisted in the German Air Force right out of high school and was captured in North Africa. Heinrich and I communicated back and forth via typed letters, written in English, from 2009 until his death in 2020,” said Evans.

Willert supplied Evans with numerous stories about his time at the camp.

“Heinrich was a prisoner of war in Hamlin less than a month when he helped to organize a sit-down strike to protest the fact that there was no recreation facility in the camp,” said Evans.

Willert wrote to Evans that the demonstration was a success because it wasn’t long before they had a recreation building. But like most of the German POWs in Western NY, he was moved to a different camp every six months. This was to ensure that the prisoners did not get too comfortable with their environment and surroundings, leading to an easy escape.

Gottfried Schulze another German POW arrived in Hamlin, NY sometime in late July of 1944. Evans was able to get in touch with him in 2010 and they exchanged emails.

“He had been drafted into the German Army right out of high school and was sent to Italy in time for the epic battle of Anzio. Not long after he arrived there his unit was wiped out and Gottfried was bleeding to death in a shell crater, with his leg all but severed, when U.S. medics rescued him.”

Schulze was then sent on a hospital ship headed for the United States, and on the way across the Atlantic Ocean, a German Jewish doctor was able to patch him up and save his leg.

“He tells you about that. He wants you to know that it was a Jewish doctor who saved his life,” said Evans.

Schulze was able to tell Evans things about the camp that no one else could. From there, Evans was able to determine the locations of areas within the campsite and learn special facts about the way the camp was run.

“I asked Gottfried if POWs in Hamlin were restricted to ‘spoons only’ in the mess hall like the rulebook for POW camps required. He said that Hamlin POWs had spoons, forks, and knives,” said Evans.

This was no surprise as POWs within Hamlin’s camp were treated well and many wanted to stay once the war was over, including Willert and Schulze.

“They wanted to stay in the United States after the war, but the Geneva Convention sent them back to where ‘they signed up.’ That turned out to be Communist East Germany for them, and no one got to leave there to go back to America,” said Evans.

As the echoes of history fade into memory, the story of Hamlin Beach State Park during World War II emerges as a hidden treasure. In the correspondence between Ed Evans and these former POWs, we find a bridge between past and present, a dialogue that spans decades and continents. Through their words, the legacy of Hamlin’s POW camp is preserved.

The third piece of this series will cover the reconnection of Willert and Schulze decades later.