By Maryalice Skutnik

The remainder of the German prisoner of war (POW) camp located at Hamlin Beach State Park stands as a fragile yet enduring testament to a pivotal chapter in wartime history. To fully restore and preserve this invaluable piece of history, concerted efforts must be undertaken to carefully reconstruct and protect the remaining structures and artifacts before they are lost to time and neglect.

Towards the end of World War II in 1946, every building on the site began to disappear. The sewer system was inoperable, and the water service was disrupted and buried. Nothing was ever built over it, and no roads were ever built through it. Nature had free reign and 70 years of runaway plant growth took over the site.

Ed Evans, the man behind the start of this historic site’s restoration, knows there is still much work to be done to rehabilitate this landmark.

“The North end of the camp has never been completely restored. The sawmill site still needs to be finished. The history that should be seen from that site has been nearly lost already,” said Evans.

There have been some efforts to make the history trail more accessible, but they have ended up causing more disruption in the process.

“There was a new walkway installed making it easier for people to move around the site. However, the walkway was installed next to and not on top of the original walkway. It’s like adding something to the campsite that was never there. We have already spent 16 years removing stuff from the site that was not supposed to be there,” said Evans.

Tampering with it has not only led to added clutter but has also led to further damage and destruction.

“Most artifacts were carefully worked around by the walking path work crew, but some artifacts were destroyed by the digging because the crew was not made aware of their presence,” said Evans.

Currently, there are no restroom facilities available, leaving visitors to venture into the woods for this necessity. Additionally, there is a lack of professionally crafted informational handouts for tourists visiting the site.

“All of my crudely drawn maps and charts in the handouts given out to tourists and attendees of these presentations need to be re-done by professional artists. My booklets about the camp need to be edited and combined,” said Evans.

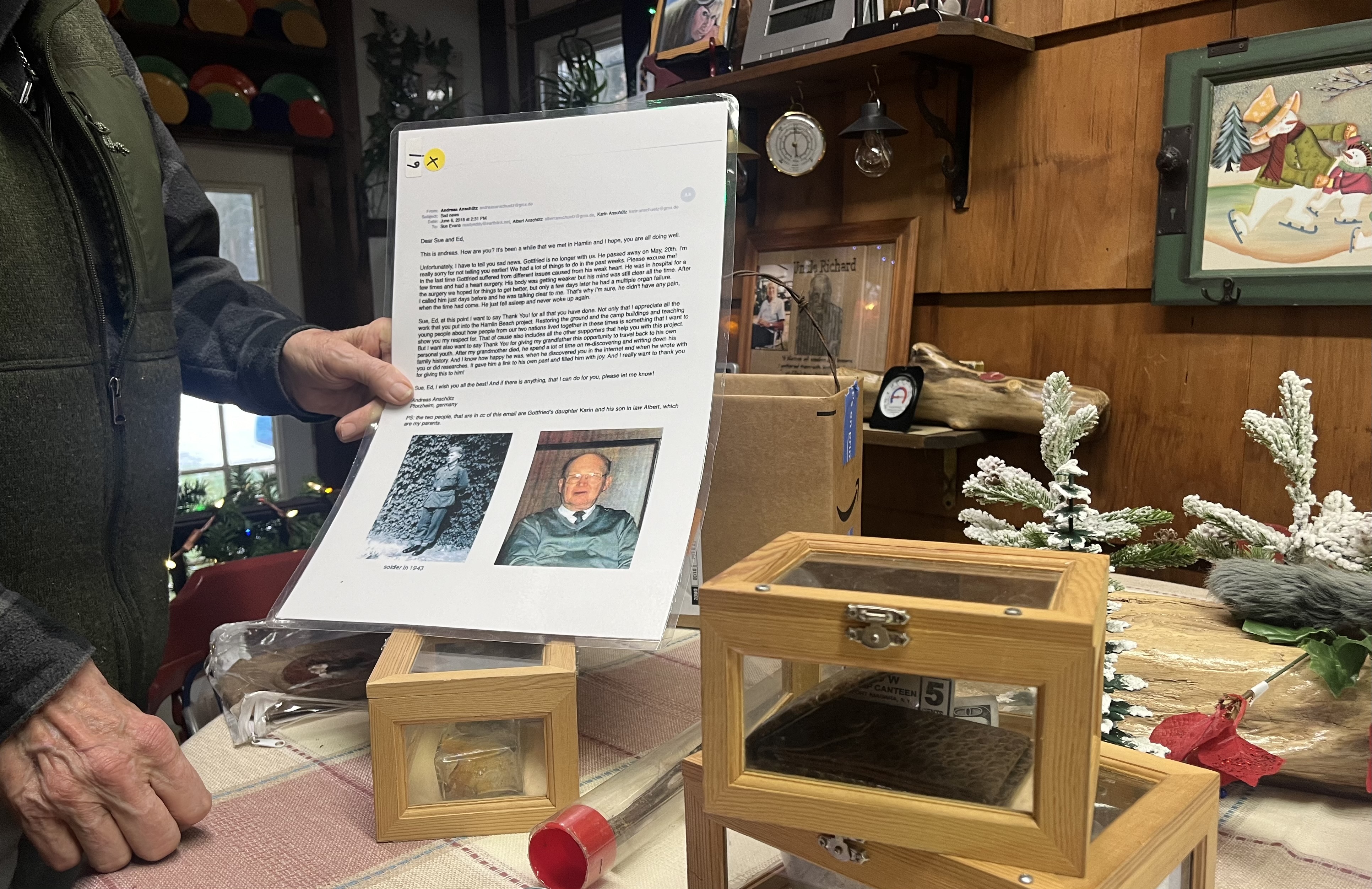

Evans’s collection of materials and artifacts will not be sent to Albany, the Friends of the State Park, or the State Park offices. He hopes to have a museum near it to hold these pieces of history.

“Until the site can be fully restored, and a museum built to hold my very extensive research collection, my house will remain cluttered with POW photos, records, documents, books, donated artifacts, maps, blueprints, emails, letters and recorded interviews,” said Evans.

Evans continues to work tirelessly to honor the memory of those who lived through this significant chapter of wartime history and to provide future generations with a tangible link to the past.