BROCKPORT, N.Y. – Marijuana has a long and complicated history in America, and although society has come to understand this psychoactive plant better, the full scope of its application remains cloaked in enigma.

The potential benefits of marijuana as a treatment for illnesses like cancer and epilepsy are not novel, but its application as a harm reduction tool, particularly in regards to the ongoing opiate epidemic, remains short on data and practice.

The term Harm reduction refers to a set of practical strategies and ideas aimed at reducing the negative consequences associated with various human behaviors. To offer a simple analogy: it would be like prescribing an impulsive shopper gift cards—or some other way that might limit their spending power.

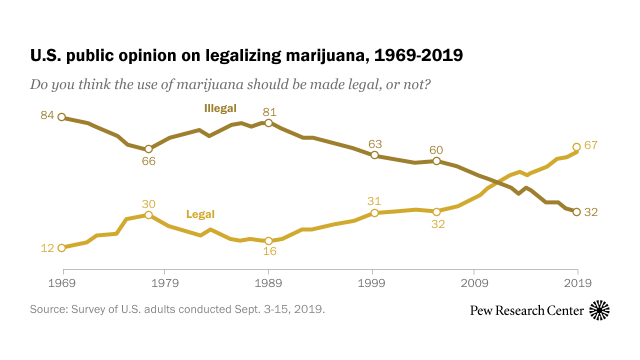

Public opinion on marijuana has shifted quite dramatically, but it still remains a polarizing subject for parts of the country. Though often derided as a “gateway drug” (or, a habit-forming drug that may lead to the use of other addictive drugs), recent reevaluations of marijuana have since challenged this long-held assertion.

With the recent sea change in New York’s marijuana policy, treatment centers in the Empire State have had to consider how this could or should influence their own policies and practices. And in a profession that is compelled by the nuanced intricacies of individual addicts and the penal system, the implementation of marijuana as a harm reduction tool requires a lot of moving parts to align.

Finger Lakes Area Counseling & Recovery Agency (FLACRA), is one such treatment agency. Nichole Hudson is an outpatient clinician with the FLACRA center in Clifton Springs, NY.

The brand-new legalization policy was, naturally, a topic of much consideration for Hudson and her colleagues. The agency had already been experimenting in-house with medical marijuana as a treatment for a range of issues.

“We were all pretty happy about it,” Hudson said. “Medical marijuana treatment is something that FLACRA implemented about two years ago. We’ve talked a lot about harm reduction and how marijuana can be actually helpful, especially for opiate users because it’s a downer. And we’ve been doing kind of our own research—within the team. You know, nothing scientific, but just looking at the numbers, our team is very excited about it.”

Hudson’s agency hasn’t officially sanctioned marijuana treatment as an agency-wide policy, but their anecdotal research has shown promising returns. The state’s new policy is sure to encourage further study and implementation.

Marijuana is emerging as an alternative to opioid antagonists like Suboxone and Vivitrol. While these drugs can be very effective in treating addiction and preventing death, Suboxone, in particular, is also an addictive substance.

“When you use an opioid, it gives you a euphoria,” Hudson said. “And with marijuana it gives you a similar feeling, but it’s not as harmful. Yes, there may be some lung issues, other issues—it’s not perfect—but scientists have shown it affects your brain in a similar way, it’s just not nearly as harmful.

Marijuana treatment for mental health has also been explored.

“Anxiety isn’t something where we’d advocate this treatment,” Hudson said. “But depression or PTSD? Yeah, we would certainly consider it.”

FLACRA treats its clients on a case-by-case basis, and many of its clients are involuntarily admitted, often compelled by the penal system.

An in-house doctor came to FLACRA from a jail program, and that level of familiarity and experience has helped to remove some apprehension regarding medical marijuana treatment for opioid abuse.

“The doctor that we utilize came from a different county—a jail program,” Hudson said. “So, initially it started off with parolees who were just getting out, who didn’t want Suboxone or Vivitrol. The doctor really had to sell that.”

Generally speaking, the parole office has been more receptive of this treatment alternative than the probation office.

“Parole is more open to the idea,” Hudson said. “The officers we typically work with, they’re very open to harm reduction, to treatment. They don’t want to put their people in jail—they really don’t. The first time we ever brought it to a parole officer, he said, ‘well, let me ask my supervisor,’ and the supervisor actually came in and discussed it with the doctor.”

“Probation is a little trickier, and their officers often look at a client’s history of compliance, and go case-by-case.”

Recreational marijuana users in FLACRA’s program typically skew younger, and many of them are involuntary, a reflection of the former policy on marijuana.

“Typically, we see kids,” Hudson said. “And I say kids because typically we see younger adults between 16 and 22 being admitted for it. Maybe about 30% of our clients. Many of these are involuntary clients often referred by probation. And you aren’t able to use substances as it would be a violation, however, it wouldn’t keep a client in FLACRA from moving on in their treatment unless explicitly requested by probation.”

Still, with the new legalization policy in its infancy, FLACRA is proceeding cautiously and continuing to operate under its general treatment standards; there’s just a new element to monitor closely.

“Every client’s treatment is different,” Hudson said. “If someone came in with an opiate disorder they would have to go through a process of group and individual sessions. We also have a psychiatrist available. If this person came up positive for marijuana, they would look at it closely. What is this doing for you? How is it positively affecting your opiate disorder?”

Even with the dramatic shift in policy, Hudson doesn’t expect to encounter any new problems for addicts as long as FLACRA is prepared and proactive.

“I don’t think it’s going to be a headache—as long as we come up with a plan,” Hudson said. “If we look at marijuana like we do alcohol, we have clients that have used alcohol and we work around that. We tried not to let it hold people back from success and graduating [the program], and I hope we treat marijuana similarly.”

“I don’t believe marijuana is as much of a worry as the opiate crisis, or alcohol, or anything like that.”

So far, so good. America remains in the throes of a devastating opioid epidemic, and drug treatment professionals like Hudson have need of every tool available to them. The early returns on marijuana as a harm reduction treatment are encouraging, and reevaluating the stigma surrounding this drug may just be the tip of the iceberg.