By: Michala Schram

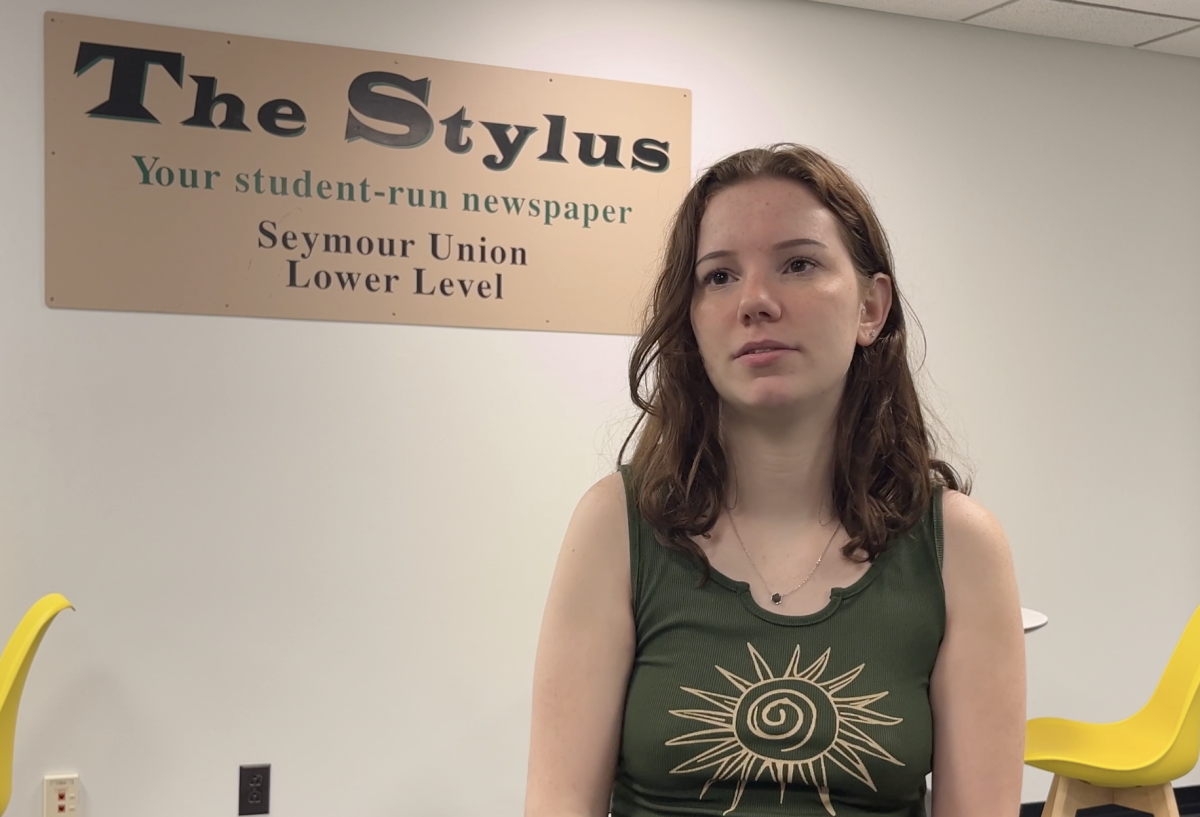

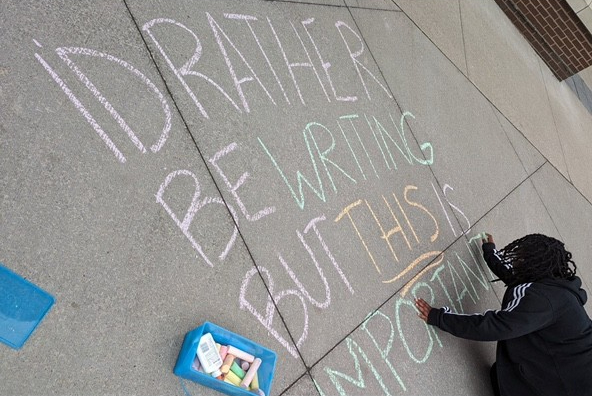

Cambrie Eckert in The Stylus newspaper office at SUNY Brockport on May 1, 2024. Canalside Chronicles photo/Michala Schram

When Cambrie Eckert was a little girl, she didn’t struggle to communicate with her parents, but noticed the rest of the world did. Listening to the obstacles her parents went through at the doctor’s office, or at the pharmacy, she heard people talking loudly or over-annunciating when communicating with her parents. She offered to help, but her parents knew her job was not an interpreter.

Student at SUNY Brockport Cambrie Eckert is a child of deaf adults (CODA). She says she felt different growing up, but always had a good relationship with her parents. She was born hearing but can sympathize with some of the difficulties her parents went through.

“I got to see their struggles in day-to-day life. I didn’t have those struggles, but I got to see what they were dealing with, and it frustrated me secondhand,” Eckert said.

Some of her earlier memories are living in Wisconsin, seeing that the Deaf community was limited in the area they lived, and made communication less accessible. She saw people assume her parents could lip read when they do not. Lip reading is a skill 30-40% of deaf people have.

“My parents could never use the drive thru at McDonald’s or [places] like that. If they pull up to the window, the person at the window would have absolutely no idea what to do, even though my parents were handing them a piece of paper [with] what they wanted to order,” Eckert said. “My parents were too anxious for that. So they would always go inside and even then it was a whole thing.”

Eckert noticed the barrier of people’s confusion that limited her parent’s communication in public. When the person her parents were talking to did not know American Sign Language (ASL), they used pen and paper to communicate. She said that was something people didn’t always want to do, and would try to talk to her to translate for her parents knowing she could hear. Eckert says she thinks her parents felt disrespected during those situations.

“So when it’s like, ‘Oh you are really wanting to talk to my daughter just because she’s hearing when you could talk to me with pen and paper like, no were not going to do that. You’re going to listen to me. We’re going to do pen and paper.’ Also, I guess as a way of [showing] it’s not that hard. Do it this way,” Eckert said.

Eckert’s father, retired professor Richard Eckert, said they chose to not have their children interpret or use an outside interpreter for confidentiality purposes, and some difficulty understanding interpreters at times.

“In terms of raising the children, one of the things that we insisted on was that they not interpret for us. That if we went someplace, and the person started talking and asked [them] to write it down, we did not want them to interpret for us. I think sometimes the kids have a lot of difficulty understanding why not, and we just felt like, why would we get them involved in adult conversations,” Richard Eckert said.

Richard Eckert said there was discrimination while living in Wisconsin. They moved to Rochester for their children and to be closer to family. With Rochester being one of the highest Deaf populations per capita, there were opportunities to meet people in the Deaf community; and for the children to meet other CODAs.

Cambrie Eckert now sees why her parents chose not to have her interpret. It shows others that communicating with them directly was important to them, even with a language barrier. It also keeps her in the role she’s supposed to be— their child.